Welcoming the Year of the Snake

The Lunar New Year, the Year of the Snake, promises for all, and for us Asian Americans in particular, a season of wisdom, transformation, and regeneration. In response, we must shed caution and silence and choose to act with courage within the places that are now and have been sources of our strength. In a time and space of division and disintegration, we must transmute our individual and familial experiences into shared self-knowledge and collective power. Over and over again we have insisted that we are no monolith, but we must decide now, against our own divisions and those that would further divide us, whether and if so how we build unity among ourselves, not necessarily in a big national or diasporic tent, but among and between neighbors.

Sixty years on from the Immigration and Nationality Act, which reordered the demographic constitution of the United States, Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial or ethnic group in the country, and the streets, neighborhoods, and communities in which we choose to make our homes are predominantly suburban. In metro Atlanta, where I live, the fastest growing Asian American communities are the most far flung from the urban core. While the push and pull factors driving this penumbral growth are well-known, and the increased numbers may be acclaimed, as if greater representation in itself signifies progress, the truth is that we have accounted for the social, cultural, political, environmental implications of our expansion. If we truly believe that our future is mutually interdependent with all Americans, we must consider three tension points and three corresponding paths forward.

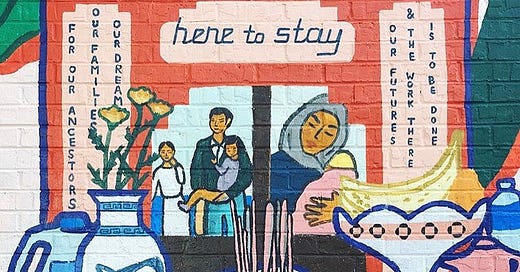

The first paradox is that even though the Asian American experience is now prevailingly suburban, the vast majority of our leading stories and storytellers, cultural institutions, and funders remain concentrated in historic, urban ethnic enclaves. This mismatch means that the communities where we are growing most rapidly are multiply under-resourced, under-represented, and too often either limited to stereotypical narratives around major cultural celebrations or eruptions of violence, or shut out entirely. Only we can, and we must, share and gather the intimate, ordinary, even mundane details of our lives in the neighborhoods, either nondescript or foreign only to the uninitiated, our families and communities have built and continue to build. To reclaim, retell, and in doing so reshape and repair our knowledge, wisdom, and power is a necessary healing and grounding process for ourselves and our communities. Knowing who we are, and where we come from, especially when where we really come from is right here, is an inoculation against impermanence, and a firmer, truer foundation for long term change.

This leads to the second tension point that the ingenuity, wherewithal, and resilience of immigrant and Asian American families and entrepreneurs have been erased from the effort to transform the quintessentially American built environment to face the advanced climate crisis. The irony is that while our communities have been discriminated against for their efforts to regenerate single-family and suburban landscapes with sustainable food practices and multigenerational housing, in more recent years we have become conditioned to the waste, segregation, isolation, and environmental degradation manifested by a toxic American Dream. The ever changing signage of suburban strip mall storefronts and monuments in otherwise decaying commercial centers are a testament to Asian American creativity, immigrant enterprise, and cultural power broadly. We must identify, document, and share among ourselves, in widening local, cultural, and generational networks, how our communities’ reimagining of these geographies of nowhere have led and will continue to lead the vital physical repair and adaptation for our new realities.

The final tension point is that the marginalization and tokenization of Asian Americans in American consciousness and culture has exacerbated our own divisions and stereotypes, further weakening our position and impact in our fragmented multiracial democracy. Negotiating a shared purpose grounded in physical proximity and local concerns, rather than investing in an imaginary broader regional or national identity and representation builds presence and power that cannot be isolated or ignored. By embracing the values of transformation and regeneration, anchoring ourselves more deeply and openly in our neighborhoods and communities, revisiting the places we have been, we will participate more fully in the local, regional, and national conversations and constantly renegotiate our presence going forward.

Ten years ago, newly unmoored from a high-control religious organization and a marriage formed in that culture, I resettled in the immigrant suburb of Buford Highway on the outskirts of the city of Atlanta. When my eldest, then all of 4 years old, asked why we kept going to Buford Highway and I told him it was because we were Chinese American and that’s where all the Chinese Americans in Atlanta went, he self-assuredly informed me that while I might be Chinese, he and his younger brother certainly were not. His declaration shattered me and changed the course of my life.

Over the next five years, I rooted myself in the Buford Highway community, defined by its eponymous six-lane, high-speed, state-owned arterial, and adjacent parking lots, low-slung apartment complexes, and strip malls. By speaking daily to immigrant business owners, attempting to knit together a coalition of small businesses and community advocates, gathering stories, collaborating with fierce immigrant artists, activists, journalists, and organizers, the organization I founded has, I hope, renewed the immigrant imprint on our neighborhood, in turn deepening its imprint on greater Atlanta and the South.

Recently, a group of Asian American community development workers, concerned by the paradox between where we are growing and where our resources are, have been meeting to articulate a way forward, which I believe must first be inward. I am grateful to Frank Lee, Jeremy Liu, and Sarah Yeung for our conspiracy and mutual support, and look forward to our ongoing work together. Join us.

It is not too late, in this year leading up to the Semiquincentennial, for those of us who may sometimes feel we are consigned to the penumbra of the social, cultural, and political issues of our day, to stay quiet, silent, and safe. But as we have seen in both the erosion of and fresh onslaughts against our democracy, not one of us is safe, or has the luxury of disengaging. From the penumbra flows the furtherance of justice. We must continue moving through these tensions, contradictions, and fear toward a more honest and more complete understanding of ourselves, our place, and our places in this living, ever-evolving experiment.